Restricted media is everywhere in the 21st century and parents worry that their children will see something raunchy or violent on a computer, but it was difficult for we pre-internet kids to see such material. In 1979 I was 15 years old, unable to get into an 18+ movie and envied schoolmates with older siblings who’d sneak them into the drive-in hidden in the boot of their car, to guzzle beer and watch…

MAD MAX!

I finally saw it in 1982 when I turned 18. Crudely made but with flashes of sheer brilliance, it was essentially George Miller‘s film school. His only formal film training was a brief film workshop (attended while in medical school in the early 1970s) where he met his creative collaborator and business partner, Byron Kennedy. Their first short film, VIOLENCE IN THE CINEMA: PART 1, was made in 1971 and their next step was to make a feature film.

Although the Australian government was funding films, Kennedy & Miller knew that MAD MAX would be a tough sell, so they sought private investors instead. Miller raised extra funds working as a mobile emergency doctor, with Kennedy as his driver, and the vehicular trauma they witnessed undoubtedly found its way into their film.

Like another former medical student turned storyteller, J.G. Ballard (author of the novel, CRASH) Miller explores the fetishistic relationship between humans and their cars in MAD MAX. Miller’s medical background (and sense of humour) are evident in ‘Mad’ Max Rockatansky being named for 19th century pathologist Carl von Rokitansky (inventor of the procedure for removing internal organs in an autopsy).

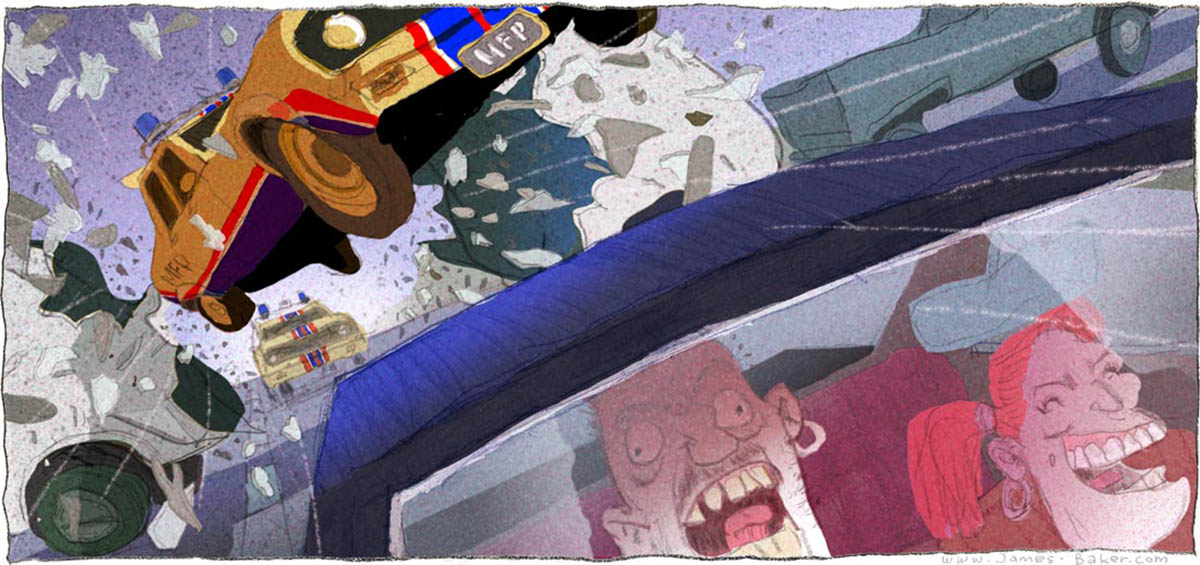

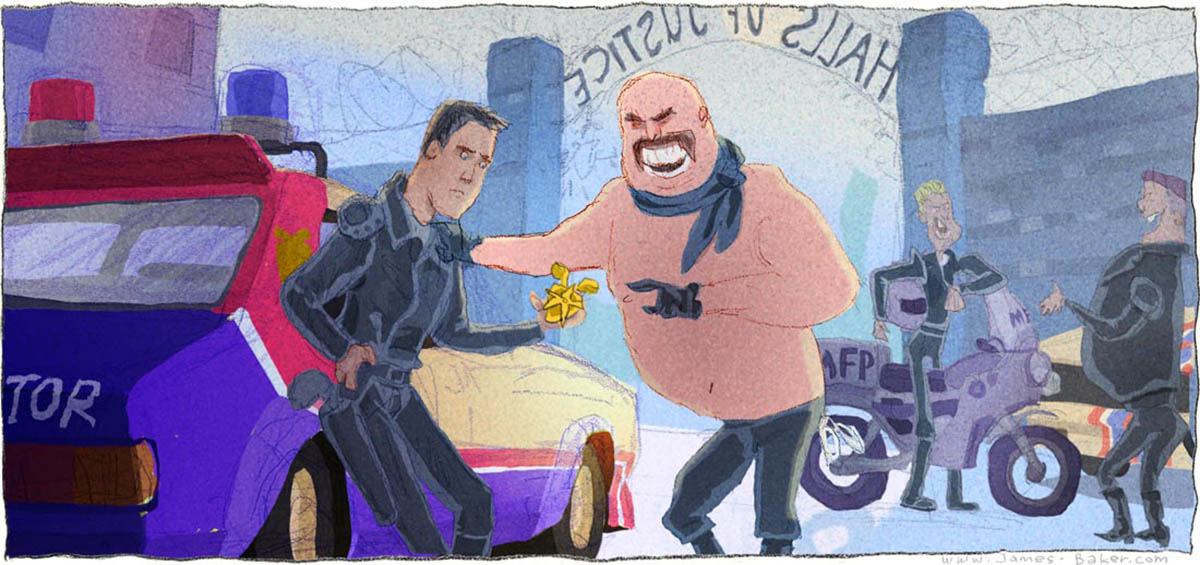

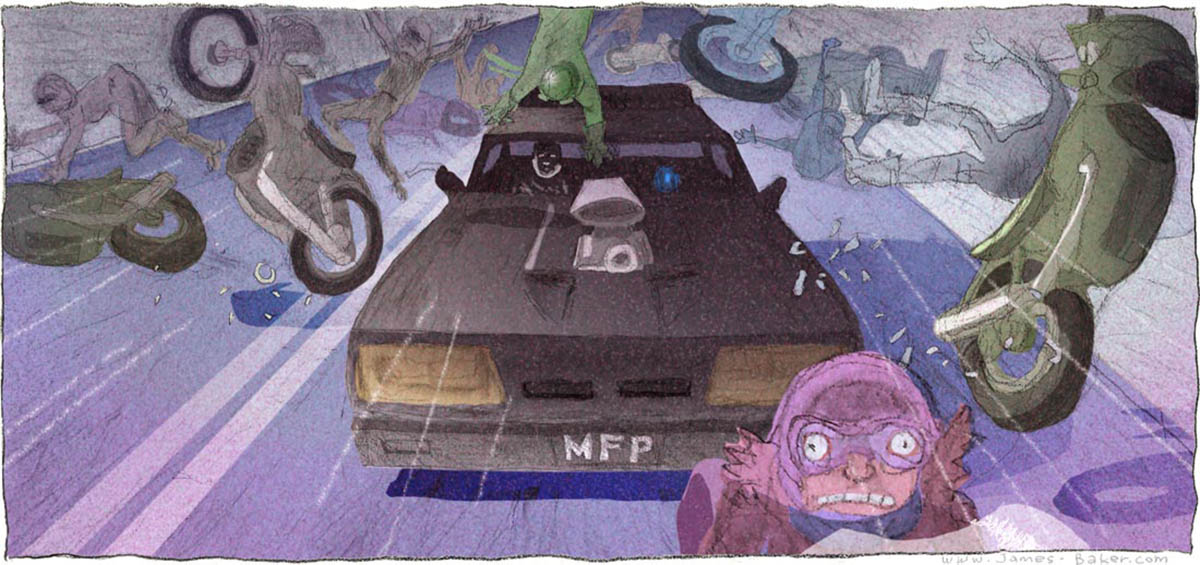

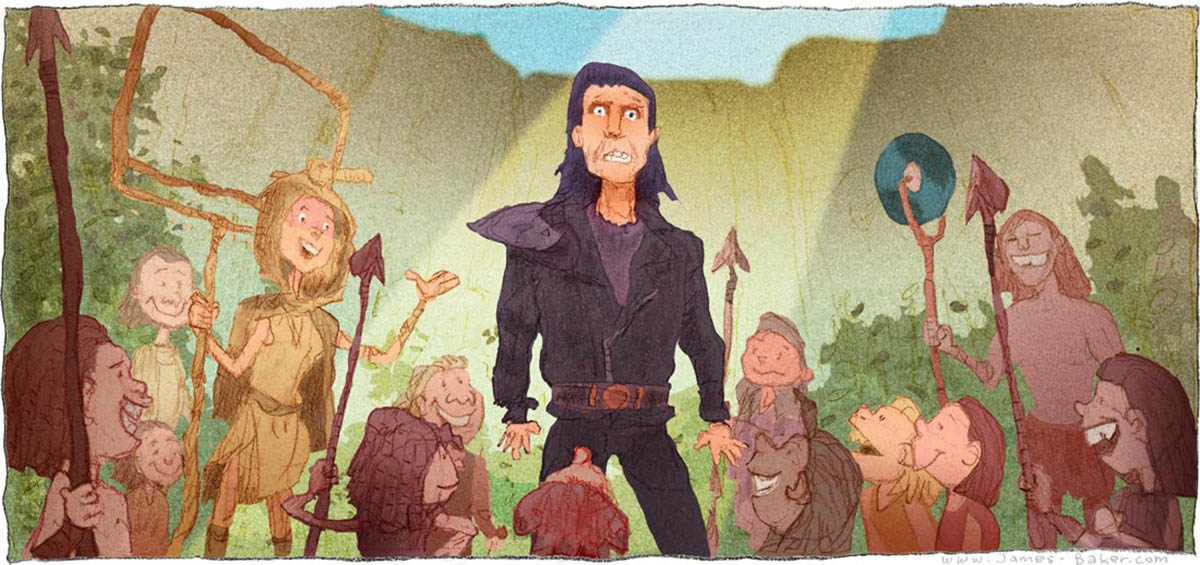

The setting is ’a few years from now’ when society is in decline. MAX ROCKATANSKY is a lawman working for the MFP (the “Main Force Patrol”) operating out of a rundown “Hall Of Justice” (complete with its own BOM BOM BOM musical sting). Though representing the forces of law & order, MFP officers look like either young leatherboys or archetypal degenerates circa 1955. Clad in Lenny & Squiggy’s black leathers. Their boss is chief FIFI MACAFEE. Though named like a burlesque dancer he looks like a circus strongman, or a bouncer at a gay bar. Burly, bald, moustachioed, and constantly bare-chested in his black leather pants, Fifi tries to keep Max focussed on the MFP mission of controlling wild motorcycle gangs. While Max worries that he’s becoming brutishly like the goons he’s supposed to stop.

Growing up in rural 1940s/1950s Australia and not going to film school meant that Miller wasn’t exposed to many filmmaking traditions (he’d never heard of Kurosawa until after making MAD MAX, for example) but he cites classic silent films and watching drive-in movies without sound as influences on his own cinematic grammar. MAD MAX was punk filmmaking, not just its gritty subject matter but its inventiveness. Full of raw energy, you can see the filmmakers learning their chords as they play. Need a stunt? Just head out somewhere remote and do it. When the director is a qualified ER doctor you deal with safety problems as they arise, and arise they did. Joanne Samuel got the role of Max’s wife, JESSIE, when the original actress broke her leg in a motorcycle accident (on her way TO the shoot, ironically) a crash that also injured and briefly sidelined Grant Page, the stunt coordinator. Miller’s bold vision was matched by the crew’s daring, and it wasn’t only the stuntmen who outdid themselves. Cinematographer David Eggby strapped himself to the back of a speeding motorbike to get a visceral hand-held POV shot of the 120kph rushing road and speedometer. These days, computers can deliver a shot from any angle the director imagines, but in 1977 it required a crew both inventive and bold enough to deliver.

A motorcycle gang wants to avenge one of their members, who died in a game of road ’chicken’ with Max. These Droogs on wheels are given to buffoonish-though-sinister antics, and led by the charismatic TOECUTTER (played with bug-eyed psychotic gusto by Hugh Keys-Byrne). Toecutter doesn’t actually have a villainous moustache to twirl, but to compensate, his lone eyebrow appears to twirl itself instead. To escape the stresses of dealing with this band of twerps-cum-perps, Max takes a holiday with his wife and infant son. But the vengeful gang, still mincing about like a wannabe Shakespeare troupe on peyote, finds Max’s family, as we knew they would.

Needing to cast and equip a bikie gang, legend has it that Kennedy & Miller simply got a real gang (The Vigilantes) and paid them in slabs of beer. I miss that 1970s-1980s era of cheap DIY cinematic invention. Where the creativity of the director and resourcefulness of the producer were the best special effects in the budget. Miller has said that initially, setting the film “a few years from now” allowed for broader action that might be implausible in the real world. And setting the story in a decaying future society explained the shabby buildings and remote locations of the shoot. Later, this became central to the MAD MAX series.

Partly inspired by actual riots during the 1970s Energy Crisis, Miller & Kennedy (and journalist turned screenwriter James McCausland) explored the idea of a society disrupted by global energy decline. And took it as far as it would go. Miller’s youth growing up in the 1940s/1950s car culture of rural Queensland, and that several of his friends died in car accidents, were parts used in the assembly of MAD MAX’s distinctive chassis. The influence of A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, BULLIT and vigilante justice films of the 1970s, like DIRTY HARRY and DEATH WISH, became the narrative engine. And Miller’s flair for visual story-telling became the nitrous-oxide fuel for one of Australia’s first anamorphic wide-screen films. Miller excelled at composing for this format, especially when the camera was moving.

The turning point comes when Max’s family is killed, and he becomes just as twisted as the road rabble he clashes with, exactly as he’d feared. While DIRTY HARRY merely flirted with the idea of a lawman crossing that line, MAD MAX goes all the way. In a climactic sequence that shows Miller’s genius for kinetic cinema, Max becomes a killer himself, hunting down the baddies one by one in his Black-on-Black super-charged V8 INTERCEPTOR.

Many critics deplored the vigilantism. Critic Phillip Adams made exploitation cinema himself (producing ‘THE ADVENTURES OF BARRY McKENZIE’) but preferred raunch over violence. His review entitled ‘The Dangerous Pornography of Death‘ called for Mad Max to be banned. Saying that it had ‘all the emotional uplift of Mein Kampf‘. MAD MAX actually was banned in Sweden and New Zealand for fears of copycat violence by real life motorcycle gangs.

For the American release, Australian voices were overdubbed (not restored till the 2002 DVD). Tom Buckley of The New York Times called the film ‘ugly and incoherent’ but TIME’s Richard Corliss praised it in his review entitled ‘Poetic Car-nage’. While critics debated its merits, MAD MAX became a drive-in hit around the world. 1970s Australian cinema was a two-step of art house (THE LAST WAVE) and grind house (ALVIN PURPLE) culminating in MAD MAX as its biggest success at decade’s end. On a shoestring production budget of AU $350,000 it made US $100 million at the box office. Before THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT, it was the best budget to box office ratio in cinema history.

Some find Mad Max too crudely made to enjoy, especially viewers who saw The Road Warrior first. However, I appreciate it as a brilliant director’s raw and inventive feature film debut. This chapter of the saga can certainly be skipped, but there’s resonance in seeing Max before he lost everything, became a ‘man with no name’ type, and the world around him, went MAD.

In any vigilante justice flick the escalation of violence inevitably gets personal- after all, we bought a movie ticket to see MAX get MAD- but the price of vengeance is that Max himself becomes a hollow man. His decency and role in society gone, the only place left for him is with the wild marauders. A wandering lost soul, he heads off in his iconic black-on-black Interceptor.

Much of the editing of MAD MAX was done by George Miller himself. Working around his own shooting mistakes during a one year editing process was painful. A lesson that would serve him well when the success of MAD MAX allowed him to make a sequel, and try again.

——–

After MAD MAX broke internationally and was compared to other stories, George Miller reflected that each culture has tales of wandering antiheroes, and began to see Max as another version of that. With a copy of THE HERO’S JOURNEY under his arm, Miller and co-screenwriters Brian Hannant and Terry Hayes set about crafting a taught script of a post-apocalyptic wanderer. A ‘western on wheels’.

After MAD MAX finished shooting in 1977, the car used as Max’s Interceptor (a 1973 Ford Falcon GT Coupe with a V8 engine and the front of a Ford Fairmont) became the property of the production mechanic. Miller bought it back for the sequel. With a wily bunch of stuntmen, the great Dean Semler as his cinematographer and the red desert of Broken Hill as his canvas, Miller made a film in the ’Outback Gothic’ tradition (of films like WAKE IN FRIGHT, WALKABOUT, and PICNIC AT HANGING ROCK) but with a post-apocalyptic angle all its own.

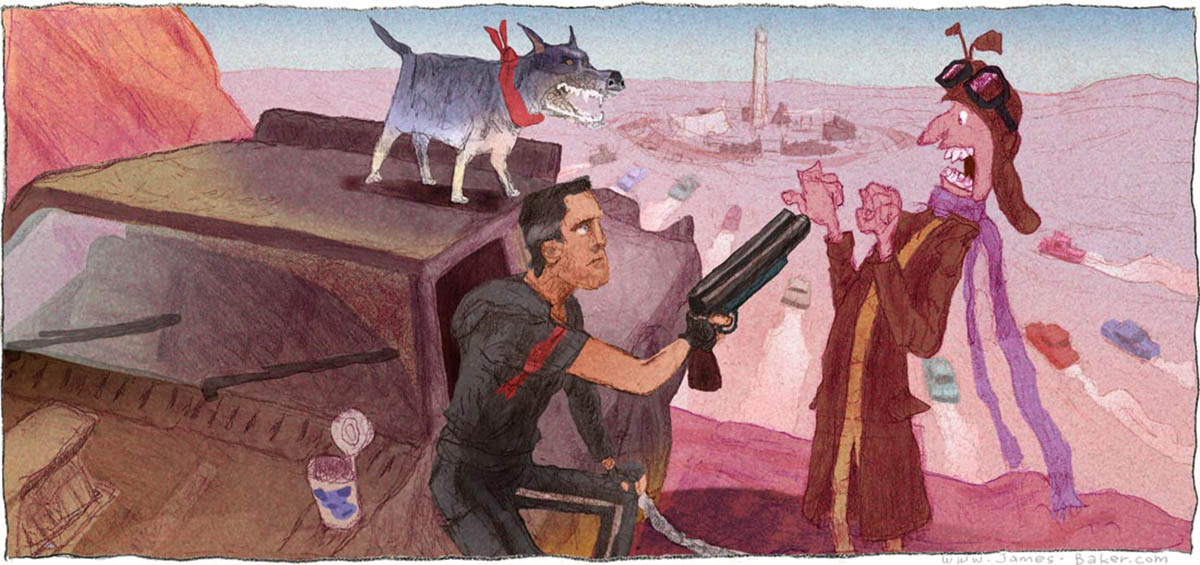

ROAD WARRIOR A black-and-white montage about a global energy crisis leading to war is shown with mono sound. Shifting to widescreen colour with a Dolby Stereo mix, focused on the ROARING bonnet-mounted Supercharger on Max’s black Interceptor. The car is now weatherbeaten. As is Max himself, and he’s acquired a Blue Heeler copilot named DOG. An even more outlandish gang than in the previous film confronts Max, but they get the worst of the vehicular altercation. Max slams on his brakes to sponge precious petrol from the wreckage with his hankie. To be hissed at by WEZ, an angry bloke with eyeliner, Mohawk, arseless chaps and twink boyfriend. They fang off on their Kwakka, popping a wheelie as they go. This opening sequence is Miller’s way of telling us that we are further down the descent to total societal ruin.

MAD MAX 2 (as it is known in Australia) came out in December 1981. I saw it in 1982 when I was 18 years old and working at Hanna-Barbera in Sydney. For the first time in my life I was surrounded by artists, and prowled the studio after hours. Fascinated by their work. I loved seeing Brendan McCarthy‘s sketches pinned on a wall and I’ve followed his comics work ever since. (He’d eventually help shape the 4th film in the MAD MAX series over 30 years later, and I’m sure a lot of the demented brilliance of FURY ROAD is his influence). He’s said in interviews that, like most people in Australia that year, he was thunderstruck by ROAD WARRIOR. It was for him the imaginative cinema moment that STAR WARS was for most people.

Seeing ROAD WARRIOR was a rush, and full-page advertisments in the Sydney Morning Herald proclaimed “It’s OUR Star Wars!” Nowadays, WOLVERINE, THOR and other characters in Hollywood productions are acted by Australians, but there was barely any Australian fantasy or Sci-Fi in the 1970s. A cheesy TV show from around 1970 called PHOENIX FIVE, and The Australian ‘Eagle pilot’ in SPACE 1999 were about it.

When the MAD MAX films burst onto screens in the late 1970s and early 1980s they had the OZ Sci-fi scene all to themselves. ROAD WARRIOR seemed uniquely Australian and established Mel Gibson as an international star, with only 16 lines of dialog. George Miller was The Kurosawa of the carburettor. The David Lean of machines. The John Ford of the chopped Ford. A visionary cinematic communicator.

In ROAD WARRIOR, towns are long-gone but there’s a vestigial community in a fortified oil refinery. This would’ve been a village of peasants in a Kurosawa film. A town of dusty frontier folk in a Leone western. Or a cavalry fort encircled by Apaches in the John Ford version. But in Miller’s film it’s a community wearing white cheesecloth. Despite pumping oil all day. Their adversaries are post-apocalyptic banditos; musclemen driving souped-up V8s, and angry bondage bikies, (including Wez, he of baboon-arsed trousers and Kaja-Goo-Goo boyfriend that we met earlier). These MTV dudes are led by LORD HUMUNGUS, a body builder in a hockey mask. He vows to nick all the goodies’ oil, but though they try repeatedly, his wasteland vermin can’t get at it. Likewise, the goodies led by PAPPAGALLO, plan to take the fuel to the coast and start a new society. But are thwarted by the surrounding bondage-clothing convention and hotrod show. Stalemate. There’s much posturing and breast-beating. Especially when Wez’s boyfriend is nailed in the noggin by a deadly razor-boomerang hurled by FERAL KID, a bloodthirsty urchin in rabbit furs and chainmail glove. Max is introduced to this inter-community standoff by the GYRO CAPTAIN, a gangly pilot with bad teeth.

Though outrageously broad, ROAD WARRIOR is a fantastic caricature of the way our society actually is. Driving full-throttle to our own brink. For all the ingenious hot-rodding on display as the leather hordes encircle the cheesecloth compound, no mechanical invention has been applied to fuel efficiency.

Wasteland barbarians have not yet figured out that driving souped-up gas-guzzlers to get the gas is a self defeating strategy. “Excuse me, Mr Barbarian guy, but why are you all blasting around in V8s?” “To get the guzzoline!” “Why do you need so much gasoline? “For our thirsty V8s!” “But why-” HeAdBuTt “No more talk!”

Perhaps the meltdown of society somehow destroyed all the minivans, Honda Civics and sensible clothing? Or.. maybe just one sand dune over from Miller’s camera there actually is a posse of equally rabid wasteland dwellers who’ve fetishised sensible mall-wear and drive solar-powered cars and electric-hybrids?

Kennedy & Miller were able to raise ten times the budget for their sequel. Though paltry by Hollywood standards this was the biggest Australian budget ever at the time. The added scope that this gave Miller, plus what he’d learned on MAD MAX and a great crew to support him, allowed his imagination to run free. In much the same way that Wez is let off the choke-chain by his boss, to somersault and headbutt goodies, hiss and run around with no pants.

The clever production design of Graham ’Grace’ Walker and costumes of Norma Moriceau made for one of the most visually distinctive (and copied) films of the 1980s. A perfect marriage of high concept and low budget. In a desolate desert setting, second hand clothing is cleverly repurposed- punk rock wear and S&M gear mix with Cricket and Rugby padding- saving on sets and costumes. While the Cargo Cult aesthetic is extraordinarily visually striking and true to the story of a society in decline.

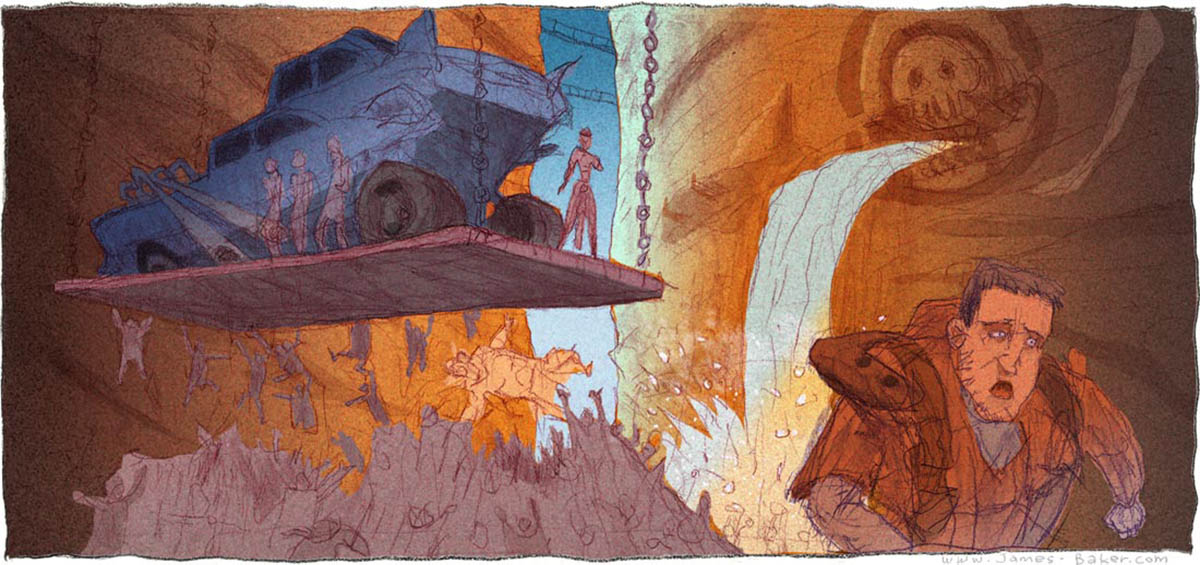

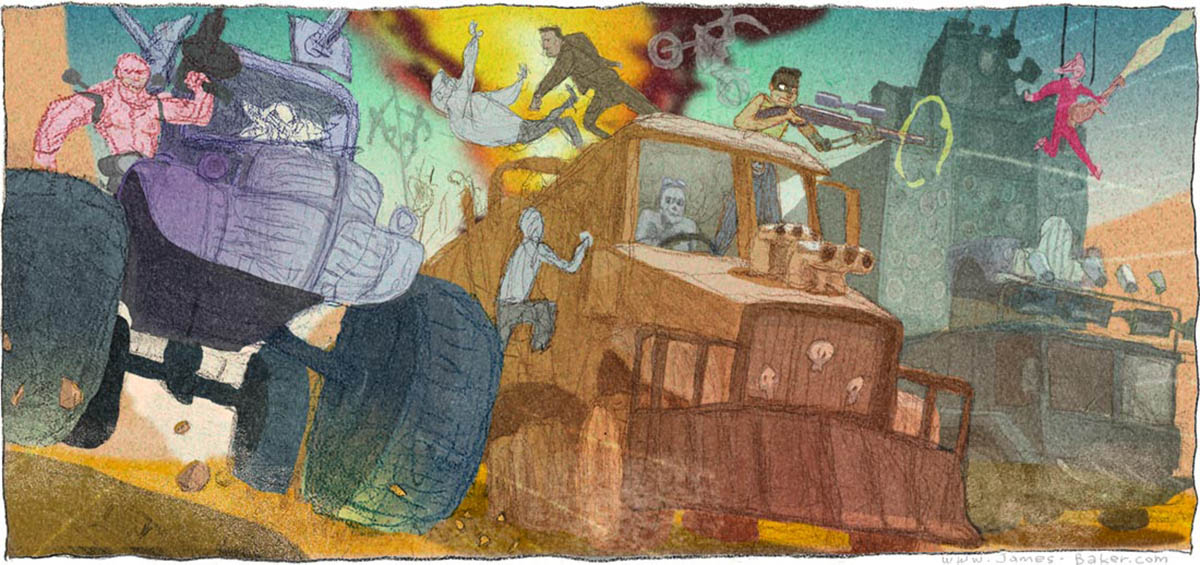

Max’s attempts to stay solo leaves him with a dead dog and a wrecked ride. The very definition of a reluctant hero with no options left, Max helps the oil-pumping community with their escape. Cue one of the most spectacular action climaxes ever put to film. That not only defined a post-apocalyptic aesthetic and genre, but established a template for ALL action films that would be strip-mined for years. While the townsfolk escape and their compound explodes, Max, Pappagallo, the gangly Gyro Captain and the delightful young brute with the killer boomerang distract the marauding loons as Max drives the tanker of gasoline out into the desert.

The 1980s was a golden era of movie stunt work, when extraordinary martial arts prowess in Hong Kong films left me slack-jawed with amazement. The Australian speciality was spectacular vehicular mayhem, as seen in the MAD MAX films, and especially ROAD WARRIOR. Stunt supervisor Max Aspin and his team of stunt-grunts deserve much of the credit for making this movie as viscerally exciting as it is.

Amazingly, nobody was killed, but there were some serious accidents. In one of the most memorable stunts, 21 year old stuntman Guy Norris, on his first movie gig playing one of the marauding bikies, hits a wrecked car, flies off his bike and launches through the air. He was aiming for an off-screen pile of cardboard boxes. Instead, he on-screen smashes his legs against the car, and cartwheels towards the camera. Causing a painful injury (a smashed femur) but the shot was left in the movie, because it was so spectacular. Norris was on set doing work a few days later (with his broken leg just off-screen). 34 years later he’d be the stunt supervisor on FURY ROAD.

Unlike the critical controversy over MAD MAX, reviews for ROAD WARRIOR hailed it as one of the best films of 1981. Richard Corliss, the first major critic to champion MAD MAX, was even more effusive in his review ‘Apocalypse POW‘ and others such as Vincent Canby and Roger Ebert followed suit.

By 1982, I thought that #2 was the magic movie number. As STAR WARS, STAR TREK, JAMES BOND and MAD MAX had all turned in second films that were far better than the originals. ROAD WARRIOR’s influence rippled throughout the 1980s. In knock-off movies, such as EXTERMINATORS OF THE YEAR 3000, THE NEW BARBARIANS, 1990 BRONX WARRIORS and EQUALIZER 2000. Music videos, and comics. Decades later, it still holds a 93% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, and filmmakers such as James Cameron, David Fincher and Guillermo Del Toro have listed it as a film favourite.

Max finally smiles when he realises that he was part of a bait and switch. The tanker he drove was full of sand and NOT the gasoline. Which was safe with the fleeing oil-pumping folk. We realise that the story is a reflection on long-ago events narrated by an old man. The brutish Feral Kid, grown to be leader of his ‘tribe’. Clearly Max made huge impression on him long ago. A post-apocalyptic SHANE.

ROAD WARRIOR was intended to be the final chapter in Max’s story, and George Miller turned to other things. Including directing a segment for Steven Spielberg’s TWIGHLIGHT ZONE. Kennedy & Miller had planned to make a post-apocalyptic LORD OF THE FLIES film, when it was suggested that Max should be the adult who finds the children. So it became the next MAD MAX instalment instead.

——–

In 1983, Byron Kennedy died in a helicopter crash while scouting locations for the third MAD MAX film. Understandably, George Miller lost interest in directing it after the death of the friend who’d helped him create the franchise. So Miller’s friend George Ogilvie stepped in to help direct.

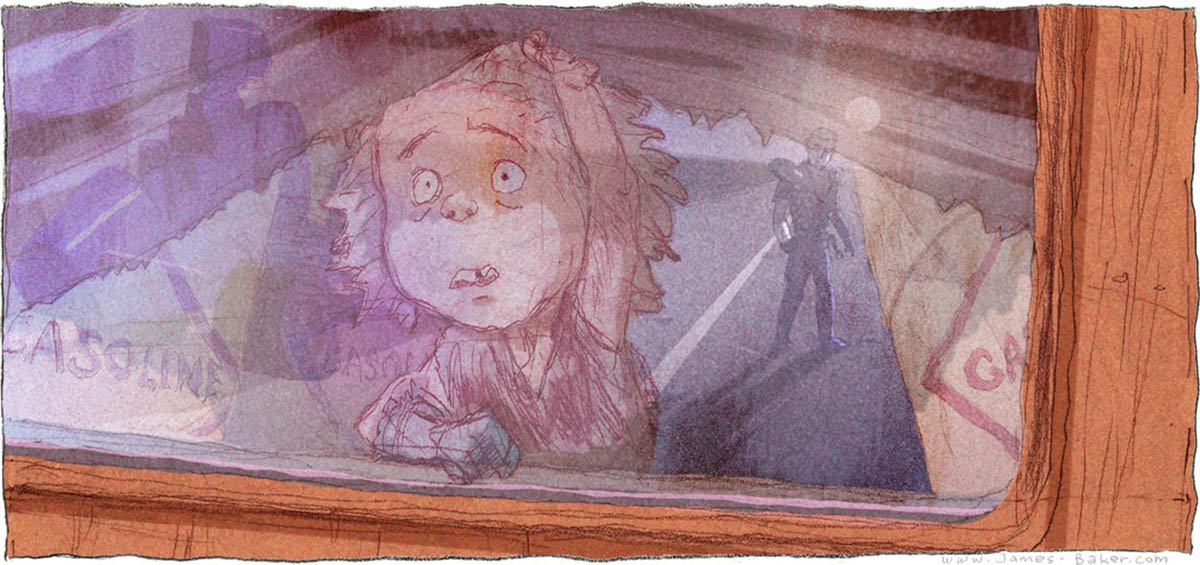

BEYOND THUNDERDOME From high above the outback, we see a car pulled by a team of camels in the desert far below. The driver atop this strange wagon is suddenly knocked out of his saddle by two flying con artists. One of whom looks like The Gyro Captain but is called JEBEDIAH and the other is obviously his child. The unseated wagon driver picks himself up, and we realise it’s Max, in Bon Jovi’s mullet. He runs off in pursuit of his stolen wagon, following a breadcrumb trail of junk tossed out the back by the monkey he’d nicked from Indiana Jones.

The trail leads to BARTERTOWN, where a bloke gets fancy with some Benihana knives and Max says, ‘Oi, the monkey isn’t the only thing I nicked from RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK’ and BLAM, blasts the knife-wielding dude right in his busby with a sawn-off pumpy.

A mate of mine did storyboards on BEYOND THUNDERDOME and said that Warner Brothers were all over it from the very start. Unlike the previous film where they’d merely handled distribution. Chasing a bigger audience for a return on their investment, Warner Brothers wanted a PG 13 rating and softened the humour, tone and action.

In exchange for this compromise, there are more production values onscreen but not always to good effect. Maurice Jarre seems an ideal composer. After all, his score for LAWRENCE OF ARABIA is the classic soundtrack of the classic desert epic. However, his score for MAX OF AUSTRALIA, with full orchestra, vocal chorus, four grand pianos and a pipe organ, sounded like a romantic broadway show in parts. The copious didgeridoo flourishes sounded like a 1980s QANTAS TV commercial, and had me pining for Brian May‘s melodramatic score for ROAD WARRIOR.

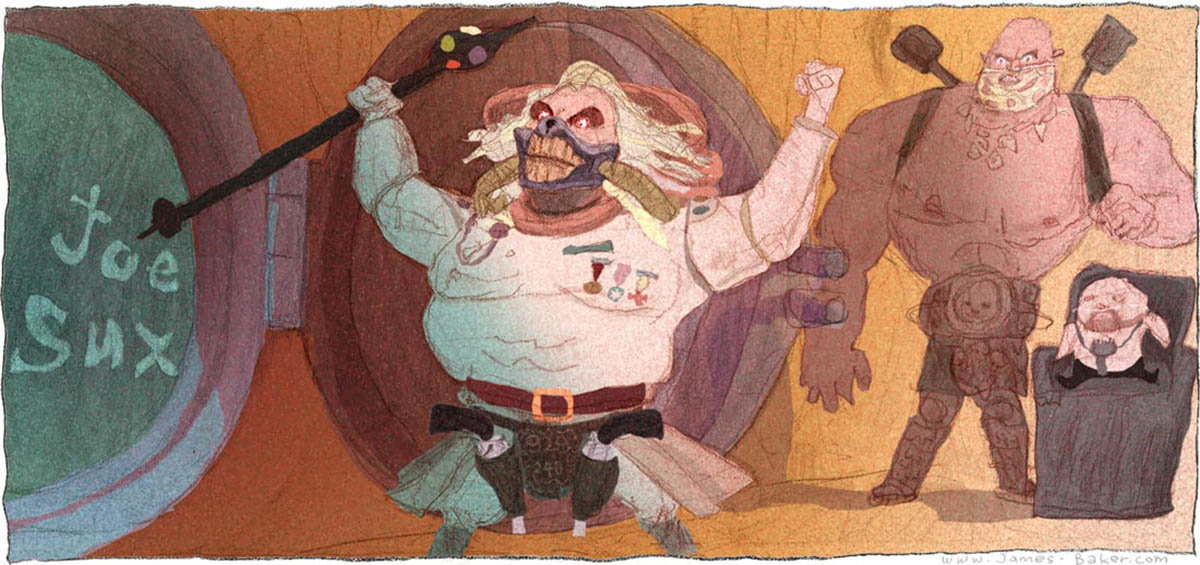

Max’s snazzy gunplay draws the attention of AUNTY ENTITY. The mayor of Bartertown, whose job is providing plot exposition to an accompaniment of tootling 80s sax riffs provided by a blind dude in a nappy. Aunty ‘splains that Bartertown has moved beyond guzzoline to a fuel provided by pigs. METHANE production is monopolised by a symbiotic duo named MASTER/BLASTER. The hulking body is called ‘Blaster’ and ‘Master’, the brains of the duo, is a dwarf even more manipulative than Tyrion Lannister. Aunty wants to topple Master/Blaster and needs Max to challenge Blaster in the THUNDERDOME. A sort of post apocalyptic gladiatorial arena cum law-court. With a Vampire Gameshow Dude as referee.

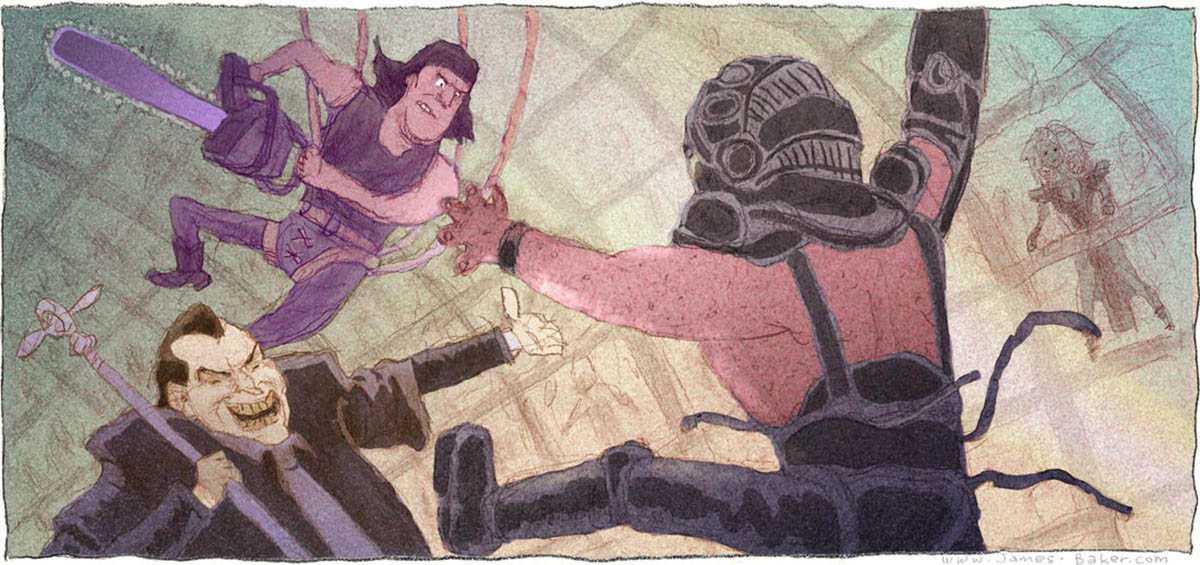

Despite the added agility from bungee cords, Max has the bone marrow pounded out of him. Then, in the nick of time he defeats Blaster. The huge helmeted and previously terrifying baddie is unmasked and; ‘AW.. he’s a total sweetie under there!’ Signifying that the RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK swipes (act 1) are over and that the RETURN OF THE JEDI swipes (act 2) have begun. THUNK! Blaster’s dead. Aunty & Gameshow Vampire Dude banish Mad Mullet from BarterTown, wearing a clown head and seated backwards on a mule..

Re-watching the opening sequences from BEYOND THUNDERDOME recently, I remembered my 1985 excitement that Max was set free from vehicular chases to be an action hero. That could deal with various conflicts in a potentially unlimited number of different ways. BEYOND THUNDERDOME’s many great ideas that entered the cultural vernacular are all from its opening sequences.

Such as the word ‘Thunderdome’ itself. Meaning an intense throwdown (“Bro, my employee review was a total Thunderdome.” or “My girlfriend went Thunderdome on me at her sister’s wedding” etc). There’s been an actual BEYOND THUNDERDOME inspired fight venue at BURNING MAN. Speaking of that, it’s hard to imagine Burning Man looking as it does today- or even existing at all -without this movie (Burning Man today looks like a snapshot of Bartertown 1985).

BEYOND THUNDERDOME has phrases that I still hear quoted today; “Two men enter, one man leaves” or “Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, DYIN’ time is here!” and so on. Despite some patchiness here and there, the recent re-watching of the film was very entertaining. Until Max gets banished from Bartertown. Then I suddenly remembered.. “Oh no…”

Max is found by an oasis of wholesome kids in blonde dreadlocks. The traditionally spare dialog of MAX movies is replaced with the constant jabber of Blonde Ewoks in a RIDDLEY WALKER pidgin, as the cute primitives mistake Max for their messianic saviour (IE: RETURN OF THE JEDI swipe #2). The leader of the Lost Children, SAVANNAH NIX, pouts when Max denies that he’s their saviour. In frustration, she and fellow believers head into the desert looking for the promised land. Obliging Max to follow, and they all end up back at Bartertown..

The idea of Max encountering a LORD OF THE FLIES Tribe of Lost Children might have worked, if the kids had resembled the Feral Kid. Wild, yet appealing in a brutish way. Never playing for any sentimentality whatsoever. Unfortunately, the Tribe of Lost Children is straight out of PETER PAN. Very wholesome, very blonde and very boring.

BEYOND THUNDERDOME lacks any charismatic villain, like Toecutter or fantastic henchmen like Wez. Perhaps the film may have worked better starting with a classic MAD MAX vehicular chase that introduces Max to (a less annoying) band of kids and climaxes with the THUNDERDOME fight? With some editing, even the version we have could be made a lot better (I wonder if there’s a fan edit of this film?)

As it stands, it’s full of good bits but lacks the cohesion to be truly great. 1985’s BEYOND THUNDERDOME was a replay of the 1983 end-of-franchise souring of RETURN OF THE JEDI. Both trilogies started tasty, got even tastier, then ended with an undercooked third course.

Whether this was due to two overseeing-companies (Kennedy/Miller & Warner Brothers) or the merging of two storylines (MAD MAX & sci-fi LORD OF THE FLIES) or the merging of two Georges (Miller & Ogilvie) something was awry.

It’s tempting to think that if Miller had directed the entire thing it would have worked, but George Miller himself credits Ogilvie as a mentor (they’d collaborated on several mini series BODYLINE, THE COWRA BREAKOUT, and THE DISMISSAL). Miller claims that BEYOND THUNDERDOME is his favourite of the three 1980s Max films.

Though it’s definitely the most ambitious, and there’s a great movie in there struggling to get out, it is (for me) the least satisfying. However, I credit the 1980s MAD MAX films for trying something very different with each movie.

The MAD MAX franchise swipes from itself (Act 3) when in the last 15 minutes of BEYOND THUNDERDOME a ROAD WARRIOR-style truck chase is tacked-on for the climax. Having helped another group trying to build a viable community, Max is left behind yet again. As the annoying kids fly away with Jebediah to establish a colony in the nuked-out shell of Sydney.

It seemed that the MAD MAX series was complete, but in the late 1990s/early 2000s a fourth film was rumoured. MAX had owned the post-apocalyptic film genre back in the 1980s. But after we’ve had THE ROAD, the PLANET OF THE APES reboots, TERMINATOR reboots, the I AM LEGEND reboot, INTERSTELLAR, HUNGER GAMES and a horde of ZOMBIE movies, would MAX have anything fresh to offer?

——–

I’d followed the on-again-off-again MAD MAX reboot saga in the early 2000s. Mel is not interested. So a grown-up Feral Kid movie is planned, possibly starring Russell Crowe. Then Gladiator happens, Russell gets huge, and Russell is out. Mel is back in, but September 11th 2001 happens, which kills the US dollar and Max’s budget. Mel is out. Heath Ledger is in. Heath is dead. Mel is back, but Mel melts down, and Mel is out. Tom Hardy is in. Then, as Wasteland production finally begins, the desert at Broken Hill is suddenly covered in wildflowers. Delaying production, for a year. Everything that could go wrong did go wrong and then some.

Meanwhile, in that same period, many of the fantastic cinematic worlds of my youth were mauled by their original filmmakers. STAR WARS, ALIEN, INDIANA JONES.. I was both interested in, and afraid of being let down by FURY ROAD, and tempered my enthusiasm right up until the theatre lights dimmed on opening weekend..

FURY ROAD Film franchises are rebooted every few years, restating the ‘origin story’ each time, but not so with the first MAD MAX movie in three decades. George Miller allows us to briefly absorb a scene of Max and his iconic Interceptor. A two-headed lizard scurrying in a barren desert shows the effects of nuclear war. Max stomping and EATING that same lizard shows how far he’s fallen since DiNKi-Di dog chow was his favourite food. Then the movie starts. Anaemic marauders chase after Max, capture and enslave him in THE CITADEL. the crib of IMMORTAN JOE. He’s the meanest desert warlord since Jabba the Hutt. Demonstrated vividly when Joe applies Trickle Down Economics on the desert-dwelling saps below. These are the random citizens we saw in the first MAD MAX movie, who now pick through the dust for scraps left by the muscle men in hotrods. There’s evidence of nuclear fallout in the the chronically sick WARBOYS, and the infertility/breeding obsessions of the villain. While tooting on an asthma inhaler (nicked from Darth Vader) Immortan Joe discovers that his 5 WIVES have been set free by one of his hench-lieutenants named FURIOSA, escaping in her truck. The WAR RIG.

FURY ROAD was utterly bonkers in the best possible way. Fever dream imagery strung on an action-narrative thread, where each action and shot were intricately choreographed. Like an insane diesel ballet. Emotions and themes were expressed in a dance of human bodies and auto bodies, done with real vehicles and flesh-and-blood stunt crew. Elevating it to another level of beauty and wonder. I’m often mystified by real dance, actual poetry, true opera and genuine ballet, but respond to poetic balletic and operatic qualities used elsewhere. Such as this nutty masterpiece.

George Miller once said that he wants to make pure-cinema films, understandable to foreign audiences even without subtitles. That’s exactly what he’s done. MAD MAX’s post-apocalyptic world, where civilisation and humanity have been stripped bare and the protagonist is reduced to his monosyllabic basics, is a laboratory for Miller to explore the limits of non-verbal cinematic communication.

Zach Snyder’s SUCKERPUNCH, or the Wachowskis’ SPEED RACER were praised by some as pure kinetic cinema, but left me utterly cold. I suspect that Michael Bay has always strived to make a film like FURY ROAD, but all he can manage is a Michael Bay movie.

What FURY ROAD has, that so many similar similar movies lack, is clear visual staging, superlative action choreography, and inspired editing. Resulting in a transcendent cinematic experience. Filmic visual language, and the boldest world-building since 1977’s STAR WARS, tell us all we need to know. With hardly a word spoken.

In the 1970s-1980s MAD MAX movies, Max had witnessed the end of society. Thus he’d have been of the same generation as Immortan Joe. Although Mel Gibson has fallen from grace in recent years, an older weatherbeaten Mad Mel would’ve been interesting here. Mel’s recent rocky history might’ve added interesting shadings to this story of a broken man who redeems himself. But Tom Hardy was incredible. And I quickly got used to his younger Max.

In this film, Max is the same age as Furiosa, so couldn’t remember the time before the fall of society 30-40 years prior. So he may not be the same Max that I once knew. That Max was a cop with a wife and toddler son. This Max’s flashbacks were of a 10 year old girl and a variety of other as-yet unknown characters.

Various fan theories attempt to explain this, and other fan theories about those fan theories aside, the MAD MAX movies were never a ‘saga’ with a beginning middle and an end. To me, they seemed to be legends about a wandering antihero. Told by other characters touched by him.

ROAD WARRIOR was narrated by the Feral Kid. THUNDERDOME was narrated by Savannah. Both having become community leaders via the long-ago assistance of Max. There was no narration in MAD MAX, but it may have been told from the point of view of Max’s boss, Fifi. Remembering a gifted young man who fell to savagery. Becoming a symbol of the lost potential of humanity.

In FURY ROAD the narration is by Max himself. Effectively denting my pet nerd-theory, but the broader point still holds – looking for timeline continuity in the MAD MAX series is not what these films are all about. Miller may intend to change Max’s back story in this ‘reimagining’, but screen time isn’t wasted on jibber-jabber. We just need to trust Miller and hold on, because his War Rig is already moving.

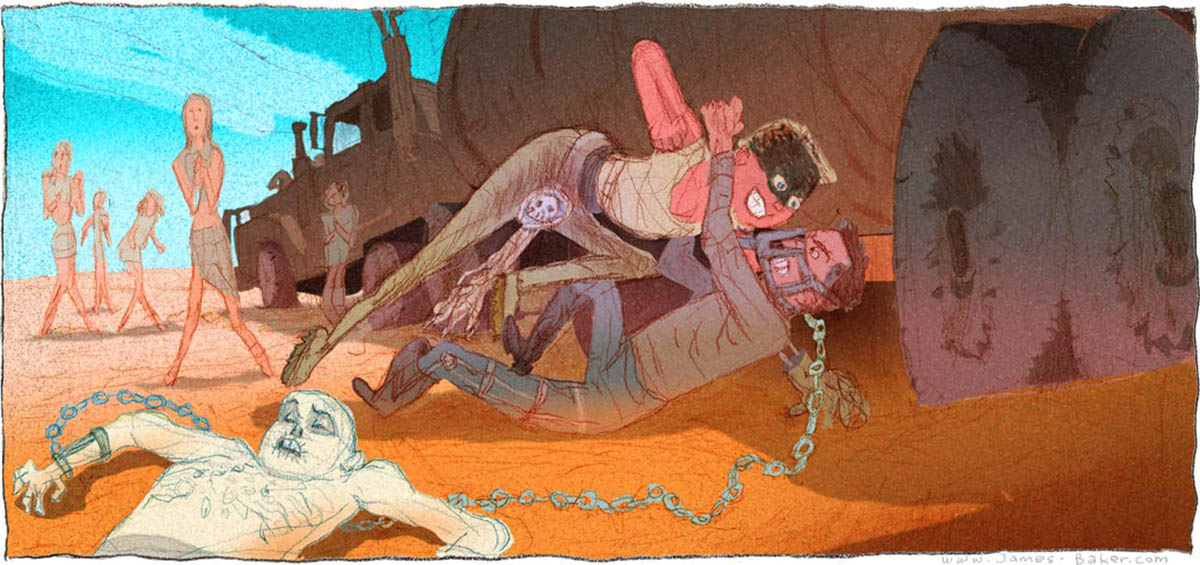

A cock-blocked Immortan Joe calls his Warboys to back him up as he chases his 5 Wives. Who are high-tailing it to a promised land called THE GREEN PLACE. The most anaemic Warboy of all is NUX. Who uses Max as a mobile blood-bag, strapped to his ride. Immortan Joe has the management style of Joe Stalin. But any warlord who has a blind guitarist and albino taiko drum crew as part of his war party has a lot of post apocalyptic panache. Meanwhile, the chase enters a cyclone and Max gets free. Only to have a savage brawl with FURIOSA.

From the beginning, Miller set his MAD MAX films at an unspecified point in the future so he was not bound by mere realism. They are broad, operatic and even cartoonish. But within that neo-mythological framework, Miller explores real-world issues. Many viewers respond to feminist themes. Clearly, Max has come a long way since Phillip Adams accused him of being ‘a special favourite of rapists, sadists, child murderers and incipient Mansons‘ in 1979.

While some male fans groan that their macho-male-movie-icon has been reduced to a supporting character in his own movie (and to women, no less). These angry boys in their “No Gurlz Allowed” treehouse forget that Max was always a passenger in stories driven by other characters’ goals. Max’s boss Fifi in the first film. Papagallo in the second, and Aunty Entity and Savannah (yes, women) in the third.

I admit to an internal groan when Charlize Theron was cast. Out of fear of Hollywood meddling, THUNDERDOME-style. Plus, I’d been soured by her role in PROMETHEUS. Another franchise restart by a 1970s director-hero that was (for me anyway) a total clunker. I need not have worried because Charlize Theron was utterly fantastic in this movie. Using her dancer training, she expressed so much in movement. Nuanced acting evoked the complex inner life of the marvellous character Furiosa, all with little dialog.

Some dismiss FURY ROAD as merely a ‘two hour chase sequence’. However, watching two hours of complex action staging and never losing sight of what is actually happening is extraordinarily rare. In most action movies today, both the objects moving through frame and the cameras themselves flail in an attempt at dynamism. Only creating an incoherent mess. Batman enters, there’s a flurry of shaky-cam shots, and 10 baddies are suddenly on the floor. In FURY ROAD, Miller trusted us to figure out the details as we watched. We could follow because he gave us the information to do so, visually. This craftsmanship alone would have left me in awe of FURY ROAD. But it also had astonishing thematic and emotional weight embedded in its beautifully kinetic Busby Berkeley routine.

In a standard action movie, the action is sandwiched between moments of character and plot development. FURY ROAD attempts to advance character and plot through the action itself. This clearly doesn’t work for everyone. For me, though this ‘two hour chase’ is brimming full with stories of human desperation and redemption. The healing power of empathy, and that to truly overcome oppression the answer is not escape, but to change the status quo.

Max grudgingly becomes Furiosa’s ally and helps her and the 5 Wives fight off the BMX Bandits and the Spiky-Car Club. Cirque du Soleil collides with a mobile Monster Truck show, as every colourful kook in the outback is after them. Max, Furiosa and the 5 Wives finally escape from this rolling Burning Man and Survival Research Laboratory parade. With some boy-howdy fancy shootin’ and Smokey and the Bandit style purty drivin’. They arrive at the fabled Green Place, but Furiosa is bummed to discover that it’s dry and shitty-looking as everywhere else. The consolation prize is meeting some really cool old bikie grannies called the VUVALINI. Max finds a lightbulb in the desert and holds it over his head. ‘Hey, Let’s turn around and storm Joe’s Citadel!’

Internet articles cite ‘secrets‘ that make FURY ROAD work (‘It’s the editing!’ or ‘It’s the framing!’). Which is like saying that the secret to Gene Kelly’s tap dancing is his right foot. As with any complicated process it’s the coordination of many steps that creates cinema magic (a much less catchy title for a Vimeo video).

FURY ROAD rises above other action movies due to clarity. Its various pieces fit seamlessly together as a unified whole. The ‘secret‘ to the flabbergasting Hong Kong films of Jackie Chan, versus his flatter Hollywood films, is that Chan was empowered to approach his Hong Kong films holistically. Involved in direction, and stunt-coordination, and performing, and editing. Whereas in Hollywood he was simply an actor/stunt performer. The career of Buster Keaton too shows a contrast between amazing films where he was involved in the entire process, and his later MGM films. Where Keaton only had limited input. FURY ROAD works because George Miller’s vision was applied throughout all phases of production:

STORY: George Miller wrote FURY ROAD without a script but storyboards were the equivalent. Allowing all elements to be planned visually long before photography began. Comics/storyboard artist Brendan McCarthy was credited as co-screenwriter, because Miller appreciates visually-scripting for a visual medium. An approach dear to my heart. (Many animated projects I’ve worked on were largely written with visuals. Whatever the credits say, the script often transcribed storyboards. Rather than the other way around). DESIGN: Production designer Colin Gibson and costume designer Jenny Beavan did amazing work that facilitates the fast cutting. The Warboys’ distinctively anaemic pallor not only works for the post-nuclear story, but allows them to ‘read’ clearly as they leap about. Vehicles to each had a distinctive silhouette. This wasn’t simply about looking ‘cool’, but looking cool in service of clarity. Cinema is images in time, and design is important. The audience could visually process the fast-cutting because of design choices as much as anything else. STUNTS: The long production delays allowed stunt coordinator Guy Norris to run computer simulations. To test safety and coordinate the weights of stunt performers and vehicles. Then those stunts were practised over and over again, before the beautiful butoh dance of human bodies was eventually caught on camera. CINEMATOGRAPHY: Miller knew that certain sequences would be edited incredibly rapidly. So traditional composition rules were broken to centre the action. Because the human eye takes time to adjust to the composition of each new shot. Cinematographer John Seale talked Miller into multiple secondary cameras to capture the action. Miller didn’t want yet another drab monochrome post-apocalyptic movie, so the only other place to go was supersaturated. The distinctive teal and orange colour palette of the movie is the work of Colorist Eric Whipp. EFFECTS: Having made action movies in the analog 1980s. Then worked in computer animation in the 2000s, Miller was supremely qualified to use both digital and practical effects, each to their best advantage. Digital effects were used to enhance the landscape, combine shots, remove stunt rigging and for greenscreening Charlize Theron’s prosthetic arm. Even the sequence which is obviously heavily CGI, the dust storm, was shot practically first. EDITING: Margaret Sixel‘s background is as a documentary editor. Her skill at sifting through loads of footage to find the ideal cut, was used to great effect, when 480 hours of footage supplied by Seale and Miller were whittled down to 2 hours and 2700 shots.

Furiosa finally confiscates Immortan Joe’s asthma inhaler, but she’s fading fast due to her accumulation of wounds. Then, in the most touching post-apocalyptic moment since WALL-E, Max heals her with his own blood. Furiosa returns to the Citadel a conquering hero, and waves goodbye to Max as he rides off into the sunset, like a YOJIMBO of the Wasteland.

Max, Nux, Furiosa and the 5 Wives were tools of the system but inverted the roles they were exploited for. Nux was taught to sacrifice himself for Immortan Joe, but used this Kamikaze role to thwart him instead. Furiosa was a lieutenant of the Citadel but used her trusted position to liberate its victims. Max was as a mere blood bag for the Warboys, but used this role to nurture his former adversary Furiosa back to life. The implications for broad societal change are clear.

FURY ROAD can also be seen as a rebuke to Miller’s filmmaker colleagues. As if to say; “You may be working on a mere franchise movie, nevertheless you should imbue it with ingenuity and excitement, and some challenging themes as well.”

Innovative films of the 1970s and 1980s became the template that Hollywood still regurgitates decades later. This sad trend could be exciting if even half those ‘blockbusters’ were made in the spirit of FURY ROAD.

When so many of my filmmaker heroes have made un-engaging films in recent years, I’d wondered if directors inevitably lose their edge with age. But feared that the problem was actually my own jaded soul. However, in a gift from George Miller, I was immersed in wonder by a film at the age of 51. And learned that a 70 year old director can still give a masterclass in action filmmaking.

Seeing this director who dazzled me in my teens do it again in my middle age is one of the many pleasures of FURY ROAD. Even though Phillip Adams still hates Max, most other critics are enthralled by George Miller’s film. After redefining action cinema in the 1980s, Miller went into animation and has not directed a live-action film since 1998. Now he proves that he’s still one of the great directors of his own generation, and serves notice to the current generation too.

It’s sad that George Miller says he only has two more movies left in him at his age. But I eagerly wait to see what they’ll be. Whether about pigs, penguins or ’pocalypse.

Here is a great 30 min documentary on the stunts of FURY ROAD. Many scenes that may have appeared to be too outlandish to do any other way than CGI were actually done practically, or assembled from many separate practically shot scenes:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yKAHGwCyamc&list=LLRSJLnaQATbs75NHM7AHLvw

Another very good documentary for anybody who wants Mad Max material is THE MADNESS OF MAX, which is on iTunes. This documentary deals only with the first film, and the barebones, seat of the pants, low-budget, guerrilla filmmaking used to get it made.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9c71yXw66fM

Most people probably know about BURNING MAN and of course it looks a lot like Mad Max’s BARTERTOWN, but checkout WASTELAND WEEKEND:

http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/wasteland-weekend-2015-outrageous-post-apocalyptic-festival-inspired-by-mad-max-films-photos-1521491

There is a great interview with George Miller (interviewed by Robert Rodriguez) that was on the EL REY network:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6c_3Lr0Ymxw

Humungus has a bad day:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=14A-d5R-8L4

These are great!!!!!!

Thank you, Kev. I had a ton of fun doing these, and as a bonus, writing the essay had me knee-deep in Mad Max links for a few months.

PS: turns out that most of what I’d thought was CGI (the slo-mo exploding truck at the end, and sproinging guitar on a bungee cord) was actually practically done after all.

Here is a short compilation of raw stunt footage:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M3fLazkWCgE

“Both trilogies started tasty, got even tastier, then ended with an undercooked third course.” HAHA! love it

“We just need to trust Miller and hold on because his War Rig is already moving.”

Hmmm. What else? Alien? (First two movies only…IMHO) The Spielberg Story…?

My favorite part of this essay: “Max was as a mere blood bag for the Warboys but used this role to nurture his former adversary Furiosa back to life. The implications for broad societal change are clear, but FURY ROAD can also be seen as a rebuke to Miller’s filmmaker colleagues. As if to say; “You may be working on a mere franchise movie, nevertheless you should imbue it with ingenuity and excitement, and some challenging themes as well.”

Kev, TOY STORY is the most solid trilogy I can think of. Fingers crossed for part 4.

Nicely written, Jamie, nicely written!

I had a lot of fun writing it.

Well timed cobber! http://comicbook.com/2015/10/05/george-miller-confirms-two-more-mad-max-movies-in-the-works/

Good news! I’m off to the shops to buy a can of silver spray paint to Celebrate

Wow. The color on these! I need to study these to up my skills. So great! I love the expressions on the characters’ faces as well. Really funny and true to source. 🙂

Thanks, Lisa. The colour is obviously WAY more saturated than the movies, although FURY ROAD was actually pretty saturated too.

I like your take on it: it’s always more fun for me when artists do a spin rather than a straight up copy. Like Mel Gibson’s angry stare makes me giggle because it’s both accurate and pokes fun at it. Is he’s thinking something unpleasantly anti-Semitic… :p

Partly it looks gumby coz that’s the best I can do at present, but like you, I kinda like it when a pinup is a warped personal version anyway.

Well done, Jamie. Wonderful homage and thoughtful critique—made me want to see them all again.

Thanks, Barbara. They all hold up pretty well.

It’s a fantastic essay, and the drawings are sensational! I had to share it on my own fb, and brag about knowing you 🙂

Thanks Russell. It was actually Julia who encouraged me to illustrate this particular article in Photoshop, rather than the watercolour doodles that I’ve been doing for the last two years on my blog. It was a very valuable exercise.

this was heaps of fun to read. and I enjoyed seeing it drawn in a different style. oh the good old days. when you could hire actors and pay them with beer. sometimes i miss the seventies.

Topless beaches in Sydney, A hot chiko roll after a lunchtime surf. 3 day non stop rock concerts. having a chunder in a taxi at 3am. good times and good friends.

Steve.

Unfortunately, I just missed Sydney in the 70s. (BTW, i like your definition of good times; Topless Chiko Roll at a Rock Concert and hurling in a cab)

Steve, you might get a kick out of this Youtube video showing a montage from MAD MAX 2 set to the Aussie National Anthem:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XJ9oVck1RFo

what a great post Jamie-

so great to read your rich historical analysis of the MAX-CYCLE and your illustrations are fantastic…!

Thanks so much for reading, Mighty-D. Julia has suggested that I collect my illustrated movie essays (Star Wars, Mad Max, Star Trek etc) into a book. Might be a fun project.

Derek, you might enjoy this HUMUNGUS tale:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=14A-d5R-8L4

Well Jamie, Mad Max is still a hit and the David Bowie exhibition is on in town… Will the 70s ever end? Hard to tell… Just saw ‘The Martian’ and thought I had gone to see Robinson Crusoe… I think the secret is the DIY approach you refer to in your essay… Too much production kills off most creativity… All you really need is a good story and an imagination… I just re-watched ‘The Year My Voice Broke’ which George Miller financed… Brought tears to my eyes…

Martin, yes, its that un-slick, crafty way of doing things that I miss. The Bowie show has not landed here yet, but I’ve read about it. ‘The Year My Voice Broke’ is a personal fave.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

One thing I really respond to in all the movies, but perhaps FURY ROAD demonstrates best, is George Miller’s idea that even after the apocalypse, human beings will not lose a sense of aesthetics. They may be reduced to owning old objects, but they will decorate and revere them nonetheless, just as in impoverished areas in the world today.

I really love that idea because it echoes the truth of human patterns. There is a documentary series called Human Planet that has an episode on some desert people who take great care in decoration. Also I was surprised about the note regarding the art direction request from Miller on saturated color rather than the drab, blue grey rain most post apocalyptic movies have.

The post-apocalypse doesn’t HAVE to be a downer.

Great read! Great pics!

Thanks Matt. Feels good to finally post it. I want to fiddle with a few of the pix, but not right now

JAMIE!!!! I’ve never been a Mad Max fan…..never really liked Mel Gibson much…..but have totally been blown away buy Fury Road….we just watched it at home again as our DVD copy just arrived……cannot agree with all of your insights and comments more!! Brilliant paintings James!!!!!! What a tour de force from you in words and pictures!!

Thanks, Phil. Yes, old Mel has seriously fallen from grace lately. I quite liked him as Max, and we now know that some of the morose intensity of the character may simply have been the actor himself. Fitting, anyway. Glad you liked the essay. I really enjoyed writing it. Almost as much as watching FURY ROAD itself!

Brilliant!!!

Thanks, Jorge!

Great to know all the background on Miller himself, since my following of directors fell off in recent years. But there’s a helluva lot to be grateful for in this artist. He’s had his eye on the true prize for the whole journey.

Jamie, so many of your first viewings of the Max movies parallels my own experience. Being challenged by the point of view of the storyteller, under the adrenaline rush of pure experience.

This as an AMAZING read. The frames are so damn righteous, the entertainment value just sucks me in. Maaaaaate!!!

Ha Ha! Thanks for reading, Ed!

Wow, I really enjoyed reading this James! Your writing and artwork is brilliant!! I’ve always loved the Mad Max movies, but Fury Road blew me away! Saw it twice on the big screen and at least twice more since buying the DVD. The ‘making of’ extras were just as incredible. ‘So chrome, so shiney!

I’m with You, Glen. Always loved all the movies, but was unprepared for how much FURY ROAD was going to deliver. Over the last few years I can’t tell you how many times I was pumped to see a film by one of my cinema heroes only to be thoroughly disappointed. So perhaps my expectations had dropped. Which in a way was perfect, as I was utterly floored. And I too saw it twice (once in 3D and once in 2D) and loved it perhaps more the 2nd time. Unfortunately I did not get the chance to see it in Mad IMAX (‘San Andreas” had taken all the screens in SF). Glad you liked the essay. It was labour of love.

Fantastic post, Jamie! Really enjoyed stepping through post-apocalyptic memory lane! 🙂

Graham! glad you enjoyed it. Thanks for visiting and saying so.

Amazing essay Jamie, brilliant artwork….. I think it’s time to publish.

Arf.

Thanks, Arthur. It was a real labor of love doing this essay. Julia thinks I should collect my movie/TV essays (Mad Max, Star Wars, Dr Who, etc) into a book. I may do that when I get a few more written. I’d probably have to self-publish though.

Very excellent writing, James. As informative as it is humorous. You have obviously researched your stuff at a deep level and I give it a High Distinction. Great images as well… The rise of the left hand is upon us. Well done, mate. Very impressive stuff.

I have to say that I can only stand about fifteen minutes of Thunderdome before I’m cursing and walking away. Over production, big names and Americanisation – as fake as a three dollar bill…

Yes, THUNDERDOME is a strange misstep, and stands out even more now that there are 4 films and 3 of them are great. I probably have a tad more time for it than you do, and I do see some good ideas in there, but it doesn’t ‘gel’ somehow, especially BEYOND the first 15 minutes or so, as you say. What a pity.

Thanks for reading, Murray, and thanks for your encouraging comments.

Jamie, This was really great, man! I love how your enthusiasm for these films comes through in your writing and in your art.

Thanks Brian. Part of the enthusiasm is perhaps a hold over from a time when fantastic media was not produced in Australia at all, and the WOW factor of seeing MAX at the time. That said, I do think that Miller is a fantastic visual communicator.

http://www.firstshowing.net/2015/watch-video-game-8-bit-cinema-version-of-mad-max-fury-road/

HA! Fantastic.

Amazing writing, amazing artwork. Baci.

Thanks Lisa. I drew deeply from my vast inner wells of nerdiness..

Have you seen this

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=XJ9oVck1RFo

Yes indeed! Mad Max set to the OZ National Anthem!

Alex Petropoulos you and Renee may like to read this. I went to school with James. He is an animator in SF and has worked on many films. I think that is an understatement.

..and I’m a wonderful human being.

Cool Post

What an enjoyable read as always, Jamie!

Hey Charles! I’m glad that you enjoyed this one. I had a great time researching & writing it and doing the illustrations too. Thanks for reading & commenting!